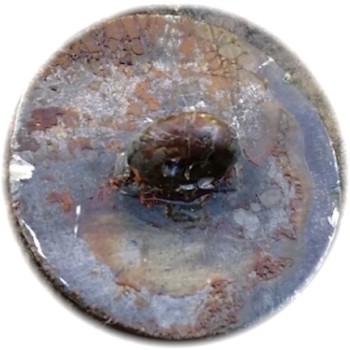

1781 Officer’s Pattern USA Button

Large Overlaid USA Cipher in High Relief

************** ************* *************

************* *************

*

1775 to 1783

Prior to the Muster of the Continental Army & State Militia Forces

************** The Patriot Movement Begins *************

************* Pre-War *************

“If you are use to Winning, then your not really a leader until you Lost”

My Take-Away from the American Revolution– Robert J. Silverstein

************** ************* *************

The Patriot movement didn’t happen quickly in the American colonies. It took several years of disparaging social and economic contract changes directed at the American colonists by the Crown and Parliament. After the Seven Years War Britain was left in a financial crisis and its subjects were being taxed at an unusually high rate. The people in Great Britain felt that the American colonists needed to pay their fair share of associated costs for the operational government in America. There was a tax burden to the English for Royal governors, Imperial officials, and the British troops who provided security against the French and Native American Indians. A tax would need to be introduced to offset some of these associated government costs.

Glass Sleeve Liberty Button Insert

************************

In the American colonies not only was there a widespread class stratification, but there was a second class citizen status that existed. Under British law European migrants were to socially have a 2nd class citizenship in regard to native born British citizens that were born in England. This left American colonists politically and in often cases economically disadvantaged to their British counterparts. When Parliament enacted the Sugar Tax of 1763, the Stamp Act Tax of 1765, and the Townshend Duties series of tax laws the American colonists saw themselves as being targeted by the British in England.

In their attempts to change these tax laws through political channels it proved to be a meaningless superficial exercise that was powerless in the legislative body in Parliament. Their pleas for social contract decency and economic tax relief would fall on the most part on deaf ears. The American working class with 2nd class citizenship had no power. They were forced to rely on America’s newly landed gentry to protest. As 2nd class citizens with some economic power they tried to use their limited influence to get the proposed laws rescinded by Parliament. This lack of equal political rights would be the root cause of a British civil war in the American colonies.

British Tax Stamp Directed at American Colonists

************************

In 1763, the Sugar Act was introduced to a firestorm of bitter indignation by the colonists. The enforcement of the Molasses Act, which was actually passed earlier in 1733, would now be enforced. In the colonists eyes they knew this tax existed, but it was really never effectively enforced or sidestepped by trade merchants. So, when Prime Minister George Grenville increased the tax with the Sugar Act he cleverly made an enforcement provision for Imperial officials to abide by. This alarmed the colonists who always evaded this tax because they could no longer sidestep it with the enforcement measure in place. The British Parliament was just looking to collect the tax on an already existing tax that was in place for 30 years to help offset some of the colony’s expenses. In the colonists’ eyes who always sidestepped the tax argued that these new enforcement laws to collect the revenue on sugar was all part of an increasingly corrupt autocratic empire in-which their traditional liberties were threatened. In England, the British Parliament legislatures were deaf to the colonists protests. The British officials made it clear to the American colony representatives that they would not address any formal protest letters concerning age old Molasses Tax 1733, and the new enforcement measures put into effect to collect were not onerous on colonists.

1760’s Wilkes & Liberty 45 Button

In 1763, Wilkes Attacks the King’s Speech on the Paris Peace Treaty

using Radical Journalism in his weekly publication of N. Briton issue 45

The 45 would be “Perception” Associated W/ a Re-kindling of Jacobitism

************* ************* *************

The British Government emerged from the Seven Years War in 1763, the country was burdened by heavy debt. England was in a post-war depression and the taxes for it’s subjects was nearly double from that prior to the war. British merchants who were once lenient in payments were now demanding immediate collection of outstanding obligations of debt incurred by the advancement of British imported products. As a further slap in the face to American trade merchants they wanted payments to be made in British pound sterling rather than colonial currency. Wealthy British merchants were able to enforce this by using their political pull in Parliament and had them pass the 1764 Currency Act. This made it illegal for colonies to issue paper currency. This Act produced a rippling devaluing effect throughout the colonies whose wealth was dramatically reduced, and their ability to pay their debt and taxes nearly impossible.

In 1765, Prime Minister Grenville would submit to Parliament a new direct tax on the British colonies in America called, “the Stamp Act.” Unfortunately, only one member of Parliament William Pitt would raise objection to Parliament’s right to tax the colonies. This law required that all printed material in the colonies such as, legal documents, magazines, playing cards, newspapers, and other paper goods be produced on government issued stamped paper from London. The law also required it also be paid in British currency and not colonial paper. The purpose of the tax was under the guise of paying for the British Troops stationed in the American colonies and to pay the British officers who returned to London in British currency.

December 17th 1765, Stamp Act Solicitation

for “The True Sons of Liberty” to meet

Under the Liberty Tree in Massachusetts Bay Colony.

************* ************* *************

When the Stamp Act of 1765 was first proposed it hit the newspapers in New York and Boston and was extremely unpopular to the American colonists. At this point all the colonists were suffering from a devaluation of their currency from the Currency Act of 1764. In the colonist’s view they had already paid their share of expenses that was derived from the French Indian War, and this was nothing but in excess. They considered this new tax as a violation of their rights as Englishmen to be taxed without the consent of colonial legislatures. Colonial assemblies immediately sent petitions to London, and the colonists took to rioting in the streets and organizing attacks on custom houses and homes of tax collectors. They even went as far as developing a popular political-war slogan, “Taxation Without Representation is Tyranny,” which was on the mind and lips of every American colonist. A boycott of British goods swept through the colonies as an attempt to force English merchants to lobby for the repeal of the Stamp Act on pragmatic economical grounds.

The Massachusetts Town Square Elm Tree

A Patriot Propaganda Button Circa 1770’s

******* Replica Button *******

In the city of Boston Massachusetts, a protest gathering was held under an Elm Tree, and the tree would afterward be renamed, “The Liberty Tree.” The organizers of the protest would become publicly known as, “The Sons of Liberty.” They would continually hold protest rallies under the old “Elm Tree”until the Royal Governor ordered it to be cut down. This didn’t stop the Sons of Liberty from continuing to organize citizen protest rallies, they just staked a Liberty Pole where the old Elm Tree once stood. The Liberty Pole was an idea given to them by Morin Scot who was a Mason, Jacobite, and cousin to the Bonnie Prince. He would be the first to use the Liberty Pole propaganda once used by Prince Edward Stuart in 1745, when he staked a Liberty Pole in the City of New York on an earlier occasion.

After several months of protests and boycotts of British goods the Stamp Act 1765, was finally rescinded. Benjamin Franklin would make a formal appeal before the House of Commons in March of 1766, and they voted in a conditional favor measure. Meaning, in order to save face, the House of Commons would concurrently pass the Declaratory Act, which had two underlying provisions. First, it stated that Parliament’s legislative powers had the same authority in America as it did in Great Britain. This meant that Parliament’s legal authority to pass laws were binding on all the American colonies. Second, they loosened-up the directives concerning the enforcement of the Sugar Act.

1770’s

Liberty & Piece Cuff Buttons

************* *************

For a short period of time the repeal of the Stamp Act in March of 1766, seemed to quiet the widespread anarchy in the streets of the colonies. Unfortunately, there would be a renewed resistance when the British Parliament passed the Townshend Acts during 1767 & 1768. This was a series of 5 new taxes and laws over a series of months by Parliament, which was directed at the American colonies in hopes of generating new revenue. Embittered over the repeal of the Stamp Act, the Parliament tried to cleverly disguise a new set of revenue generating taxes through an indirect tax on glass, led, pain, paper, and tea, which all had to be imported from Britain. This provoked colonial indignation and led to the Boston Massacre of 1770. Afterward, there were widespread protests once more sweeping through the colonies, and American port cities in Boston and New York refused to import British goods. In response most of the Townshend Duties Parliament partially repealed some of the Townshend duties except for teas, which was retained in-order to demonstrate to the colonies that Parliament had the sovereign authority to tax the colonies.

British Stamp Act Tax of 2 Shillings & Six Pence

************************

The Parliament continued with their legislative policies to tax the British colonies without American legislative representation. This caused a resentment by the colonists and it just promoted a negative sentiment with a feeling of government corruption. British politicians in London and Imperial officials in the colonies were in the crosshairs for groups like the Sons of Liberty. Neighborhood political rallies led to the organization of groups, which would organize committees to address political and economic concerns of citizens. Sometimes neighborhood rallies would turn into mob groups who felt righteous indignation and would take the law into their own hands and attack Imperial official’s homes, British merchant shops. Some groups would act nefarious and would steal or burn ships’ cargo.

In 1773, one of the Townshend Act measures was the taxation of tea. In this new tax measure Parliament would give the East India company a tax free duty in the transport of their tea. This new tax gave the East India Company a monopoly because colonial tea traders could not compete against a competitor with a tax free status. This led to the night of December 16th 1773, when the Sons of Liberty members disguised themselves as Native American Indians, and boarded the East India Ships in Boston Harbor and famously threw the crates of tea overboard. In response, Parliament passed several pieces of legislative laws which would place enforcement and safety of British goods in the Colony of Massachusetts under direct British military control of General Thomas Gage. To the American colonists they were referred to as the Intolerable Acts.

1766 William Pitt “The Great Commoner”

America’s First Propaganda Button of Rebellion

No Stamp Act Button, Copper, 20mm. Sleeve Size.

A Propaganda Measure to Rally Colonist Support

************* ************* *************

There were very few political figures in London who would even try to champion the American colonists in Parliament. William Pitt and John Wilkes were some of the few who would use their resources and try. William Pitt was a British Statesman and supporter of Britain’s Whig faction. He was a public figure and treasured member of the British Cabinet who was known to champion citizen rights. His peers found him to be fair and balanced in his political approach against corrupt government policies. He firmly agreed with Parliament’s right to legislate for the colonies, but on the other hand he disagreed with their extension of their right to impose tax measures without the proper colonial representation. When he addressed Parliament on America’s behalf, it was said his speech for colonists’ rights was heartfelt, and his address even reached the King’s ear. Unfortunately, his fellow politicians were controlled by wealthy elites. So, his plea fell on deaf ears.

Wilkes 45 Laurel Wreath Oval Cuff Button

Both the Wreath & Number 45 Represents the

Bonnie Prince’s Jacobite Uprising of 1745

************* Laurel Wreath *************

John Wilkes was another British radical politician and journalist who supported the American Patriot movement. Wilkes was known to use his journalistic talents in the media to sway public sentiment. Oftentimes he would viciously attack Parliament’s legislative issues or King George III for his stand during the Seven Years War and its aftermath. Wilkes was very cunning and knew how to use the various instruments and vehicles of society to not only curry public sentiment, but to politically maneuver changes in society by using political figures. As a society club member he used the underground social clubs as a vehicle to induce other members in positions of political and economic authority to take actions against the King and Parliamentary legislatures.

Wilkes & Liberty 45 Sleeve Button

Found in Hannastown, Pennsylvania

************* ************* *************

John Wilkes was known to flip-flop back-n-forth on his position of being a Jacobite supporter over the years, but when he was a member of the St Francis of Wycombe (Hellfire club) he did work with many of them to undermine the King. The Hellfire clubs did have many prominent members of English society, which would work together and take action in nefarious ways to undermine the Crown and Parliament. The next 25 to 30 years would be a Jacobite transition period in London starting with the Uprisings around 1745, to the outbreak of the American Revolution in 1775. Underground societies like Sir Francis Dashwood’s Orders of the Friars of St. Francis of Wycombe member’s activities would spread from underground to an openly public domain of socially accepted behavior by Jacobite sympathizers. A number of Hellfire clubs would emerge bringing not only societal acceptance, but their revolutionary propaganda symbols turned into consumer products of support.

Wilkes & Liberty 45 Sleeve Button

Found in Hannastown, Pennsylvania

************* ************* *************

John Wilkes was able to expand his anti-British media campaign to both sides of the Atlantic. He would pen his weekly radical stance on Parliament’s legislation or bash the King’s policies in his weekly publication of The North Briton; with North meaning Scotland. Some say that Wilke’s weekly publication of North Briton had an enormous impact on the development of America’s Patriot movement. His seditious propaganda would be a sort of pseudo-voice or guide for equality to a new emerging revolutionary political culture. Wilkes probably believed the old saying, “The enemy of my enemy is my friend and became sympathetic to American rebels plight early-on. He was known to correspond and fully support the Patriot movement with groups like the Sons of Liberty.

After awhile, the American colonists had become so adapt with Wilke’s writings they would start using politically toned catchphrases in public like, “Wilkes and Liberty.” This allowed the American colonist to express their disfranchisement of British government social contracts and economic laws provided by Parliament’s legislation. This kind of catchphrase propaganda was seditious on many levels to the British ruling class in America. These bywords or embodiment phrases of symbolism would be used by recruiters of revolutionaries throughout all 13 colonies. Wilkes himself was seen as a de-facto leader of sorts or even a champion of liberty and fairness to all of British society’s commoners. In England his seditious behavior and writings appealed to the underground Gentry class. In America he appealed to the commoner who was automatically barred from the benefits of formal British citizenship. In America, the revolutionaries liked Wilkes “down-to-earth” appeal and promotion of ones liberties and equality of rights.

One can reasonably say that Wilkes pushed the bounds of British societies civility and etiquette by his constant barrage of anti-British (seditious) articles in his publication of North Briton. He constantly fueled anti-king propaganda along with his view of British Parliament legislative decisions. His sentimental persuasive writings of Parliament’s legislative injustices would be the bridge across the Atlantic Ocean. His commentary would feed right into the emerging disenfranchisement that was felt by the revolutionaries across the Atlantic in the Patriot movement. His writings would be the ground work for the grass-roots movement who was already psychologically taxed to the limit on slew of British Legislative economic decrees. Wilkes was so critical of the King he became a martyr of sorts. At one point, he lashed out so violently in his writings of the King and his endorsement of the the Paris Peace Treaty of 1763, that he was arrested for sedition and held liable for his article in North Briton 45.

After some time, England’s underground movement would finally go above ground with their anti-King sentiment and Jacobite sympathy propaganda objects. This next level in the propaganda warfare was enabled by the revolutionaries in America. (A “Leap of Propaganda” is when a set of seditious ideas for change comes from out of the shadows of obscurity and then takes root in a society’s main stream culture). In the early years of the Patriot Cause the revolutionaries would meet covertly just as the Gentry class did in England’s underground movement. Sedition was recognized by the Crown in the colonies and discordant laws were placed in effect to curtail revolutionary thoughts or behavior. The difference is that the American revolutionaries did not feel ethically bound by a British cohesive cultural etiquette that was only provided to a small class of Englishmen who had British citizenship. The majority who lacked the rights of British citizenship had no qualm for boldly airing their grievances in form of a rallying-cry in public squares or marching on in a mob-rule mentality throughout the streets. Public justice erupted against Imperial Officials, and then over time they became flagrantly violent and destructive in nature. Committees were formed in the name of equality in the face of British injustices, which were deemed outside of social contract fairness.

45 Buckles

45 Buckles

John Wilkes & Liberty

Referencing the “45” North Britain

Symbolizing Jacobite Support Within the Cause

*************

Boston Sons of Liberty to John Wilkes, June 6, 1768

“May you convince Great Britain and Ireland in Europe, the British Colonies, islands, and Plantations in America, that you are one of those incorruptibly honest men reserved by heaven to bless, and perhaps save the tottering Empire.”

There was a number of Jacobite Uprisings since 1688 to 1746, which used anti-British propaganda symbols to persuade public sentiment. These symbols were known to many colonists who immigrated from Europe to America. The 18th century was filled with transatlantic news of the British Army triumphs, as well as the news of sympathetic Jacobite movements throughout Scotland, France, Italy, and the Holy Roman Empire of the German nation states. Many Jacobites after the Battle of Culloden in 1745, came to America to take refuge and were wealthy capitalists. They were a part of the gentry class of Americans who were most likely Masonic members of neighborhood lodges. It is customary for all Masonic lodge brothers to learn all the symbols and understand all the historical context they were used for. Meaning, the origins of symbols and then their propaganda used by different world cultures and nationalities throughout time. Since, many lodges are Scottish-Rite by origin the members were most likely sympathetic to the Jacobite Cause, and would be aware of tidings (Current News) and symbol use in the underground movement in European nations.

The 1760’s-1770’s English Ouroboros

Jacobite Resistance & Restitution of the House of Stuart

Possibly the Earliest Known Introduction of the United Chain Link

13 Stripes for the Bonnie & His 12 Knights of the British Order of Garter

************* ************* *************

All of America’s early Revolutionary War symbols were the same ones being used concurrently by the anti-British underground movement in Scotland, England and France, but they were re-purposed to fit their narrative. American radicals adopted many of these liberty symbols in the mid-1760’s & 1770’s, and they were fully aware of their underlying meanings. As with other worldly cultures they changed their context to fit their narrative for their revolutionary movement. The Liberty Cap & Pole, Rattlesnake (Ouroboros Snake) Swallowing the 13 Rattles (Tail), the (Conquering) Laurel Wreath of the Bonnie in 1745, the Thirteen Stripes, and Chain Link (Both English Unity Symbols) were all re-purposed propaganda from an earlier time in history and transformed by the rebels to fit their radical movements against tyranny. Meaning, every single symbol used in the American Revolution is easily shown to have an earlier use in history, or recently in their century by Prince Edward Stuart’s Jacobites in their 1745, Propaganda Campaign in Scotland, France, Italy, and England; or the bar (stripe) and chain link from the London Secret Societies underground movement in 1760’s & 1770’s. Even Benjamin Franklin’s 1754, Join, or Die 8 Segmented Snake cartoon in the Philadelphia Gazette comes from a cut snake device wood block engraving of 1696, in Paris with the unite or die metaphor. The segmented snake would actually be repurposed a 2nd time in the New York Journal in 1774, as “Unite or Die” by John holt.

Even though the snake cartoon was not reprinted in standard English newspapers or magazines, it appears to have been well circulated throughout the British colonies in New York and Boston newspapers. This repurposed cut-snake cartoon was a propaganda chess-piece move by Franklin to gain public support as a public rally-cry for action. This would in-turn give him a desired public square momentum of debate prior to his trip on June 8th 1754, to the City of New York where he would give the gentry political class his “Albany Plan for American Unification.” As with all propaganda moves there are many other variables which contribute to it success. Such as, the Virginia Gazette later reporting Colonel George Washington’s dreadful defeat at Fort Necessity two months after the political cartoon on July 19th 1754.

Even though the snake cartoon was not reprinted in standard English newspapers or magazines, it appears to have been well circulated throughout the British colonies in New York and Boston newspapers. This repurposed cut-snake cartoon was a propaganda chess-piece move by Franklin to gain public support as a public rally-cry for action. This would in-turn give him a desired public square momentum of debate prior to his trip on June 8th 1754, to the City of New York where he would give the gentry political class his “Albany Plan for American Unification.” As with all propaganda moves there are many other variables which contribute to it success. Such as, the Virginia Gazette later reporting Colonel George Washington’s dreadful defeat at Fort Necessity two months after the political cartoon on July 19th 1754.

The 1770’s Underground Jacobite Movement in London

Resistance and Restitution of the House of Stuart

Ouroboros Circling Around an English King’s Sunburst & 13 Stripes

************* ************* *************

The American colonists were uncommonly unified for the first time on all social class stratification levels, but their manner of approach in solving their political and economic social contract problems was vastly different. The Nouveau Riche Americans like Samuel Adams and Benjamin Franklin who represented the newly landed gentry wanted to exhaust political channels while the common citizenry had a mob mentality toward political change. The gentry class was afraid of the repercussions of rebellious actions outside of normal diplomatic channels would sever future political and economic ties with England.

On the other side of the spectrum, the Royal governors and Imperial officials had the hardship of enforcing these new tax laws. Imperial officials were placed in the unpopular position of being the face of the British Parliament’s new tax laws. It was their duty to oversee that trade merchants were fully complying. Unfortunately, enforcement resulted in Imperial officials over-reaching their legal authority in-order to comply with the unpopular tax duties. They themselves would then be targeted for retribution and oftentimes were forced to flee their own homes from citizen mobs.

Sir Robert Strange Exiled in France W/ Resistance & Restitution on

Mind Designs a Rattlesnake Button for America’s Robert Scot

This Symbol was a Popular with Radicals in London’s Underground

Movement in 1760’s 1770’s. Transformed into America’s Rattlesnake

************* ************* *************

In the 1760’s the rebels lacked a macro-cohesion in their movement for a centralized leading representative for the New England colonies. Each rebel faction had their own individual known leaders, but they usually operated within their own town or city. The early roots of the Patriot movement was a series of divided factions that lacked a central leadership to represent all the New England colonies. As Parliament passed new trade laws and introduced taxes affecting citizens protest organizers would start new roots and form citizen concerned groups to represent their interests. After a while the Patriot movement started to blossom into larger numbers and began putting forth Special Citizen Watchdog Committees to counter Imperial officials governance tactics. The end-result (which in all intensive purposes was the beginning) was a formation of untrained colonists who would turn into militiamen. “The Shot Around the World,” was the opening shot of the Battle of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, which began the American War of Independence.

~ General George Washington ~

Commander in Chief of the Continental Army

One of Two Known Uniform Buttons to Still Exist

Dug at an encampment site circa. 1775.

************* ************* *************

On June 15th 1775, George Washington was elected by unanimous vote by the Second Continental Congress as, “The Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army.” General Washington was able to retain this position throughout the entire war. There were eight Brigadier Generals who were appointed simultaneously to provide military aid, Seth Pomeroy, Richard Montgomery, David Wooster, William Heath, Joseph Spencer, John Thomas, John Sullivan, and Nathanael Greene (After Pomeroy did not accept, John Thomas was appointed in his place). Also, there were four Major-Generals commissioned: Artemas Ward, Charles Lee, Philip Schuyler, and Israel Putnam.

Three days after George Washington’s appointment as General, the Continental Army would see its first engagement at the Battle of Bunker Hill with 1,200 Massachusetts State Militia troops under Colonel William Prescott. The idea was to fortify the unoccupied hills surrounding the City in-order to control Boston Harbor. The troops would first construct a redoubt on Breed’s Hill as well as fortified lines across Charlestown Peninsula. On June 17th 1775, the British would launch three attacks. The defending colonists were able to fight off two of the assaults, but on the third they ran out of ammunition and had to retreat back over Bunker Hill to Cambridge. Their defeat left the peninsula in control of the British. This early militia army that took part in the Siege of Boston in 1775, bore very little resemblance to Washington’s Continental Army that laid siege on Yorktown in 1781. General Washington was able to progressively organize, strengthen, discipline, and improve his army’s utility for engagement. By the war’s end 230,000 would have served in the Continental Army, although never more than 48,000 at one time. Washington’s Army would be supplemented by 145,000 minutemen for rapid deployment.

Congressional Lottery Ticket, Philadelphia Pennsylvania November 18th 1776.

************** ************* *************

Little known fact is that Congress printed its own money, (about 28%) of the war’s funds since 1775. Congress did not have the power to tax through the Articles of Confederation, and there was no organized national bank at this time. Even though there were several lenders to the Cause, Robert Morris & Hyam Salomon was its principal financier in America. Salomon was a Polish-Jewish who immigrated to America, and was a financial broker in the City of New York. As a well known financier he was able to help Robert Morris find purchasers of government bills, and get sympathetic prominent citizens to lend money to the government.

~ Depiction of Events on June 17th 1775 ~

The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker Hill

Boston Museum of Fine Arts Painted by, John Trumbull

************** ************* *************

*

Preface on Military Buttons

************* A *************

Buttons have been around for 5,000 years. Originally, sea shells, curved stones, and wood was used in-conjunction with a simple fastening loop of animal (ex. horse) hair placed around it to fasten it loosely. In the 13th century, the Germans introduced a more functional button with sew holes. This allowed buttons to fasten to the garment more securely, and allowed clothing to fit more snuggly against the body. This German innovation of button sew holes spread quickly all throughout Europe. Military type buttons didn’t make an appearance until the second half of the 18th century. Until 1750, it had been customary for Royal guards and armies to wear the same kind of buttons as civilians. Even though individuals could wear any pattern they choose, they sometimes would wear a specific matching pattern as their fellow in-the-service individuals.

The trend toward specialized reflective service military type buttons blossomed in the 1760’s and 1770’s. The British first introduced uniforms to the army in the 18th century. Each soldier was issued a wool coat with their own insignia or regiment numbered button; Along with linen garments in the spring and fall. The trend immediately caught on in other European countries like Spain and France, who also had established large military armies of varying regimental lines. The French military took the designing of officer’s buttons even one step farther and provided design styles comparable to their highly detailed coins. Emblems of loyalty such as crowns, cyphers, mottoes, laurel wreaths, eagles, battle horns, and so forth were introduced originally for officers, and then through popularity appeared on most enlisted men’s military buttons. From that point on both British and other European nation’s armies would use specific regimental or corps emblems on newly issued uniforms from the lowest to the highest ranks.

*

The Establishment of Continental Army

************* B *************

The Continental Army was the first national army of the thirteen colonies raised by the Second Continental Congress on June 14th 1775, to oppose the British Army during the American War of Independence. The Continental Army would go through three major establishments. The first was in 1775, the second was in 1776, and the third was in 1777, lasting to the end of the war. The members of the Continental Congress were hostile to the idea of having to continually fund and maintain a large standing army, so they curtailed enlistment durations to a year. Under the perpetual union of the Articles of Confederation Congress did not have the power to raise troops by the means of a draft. Enlistment in the Continental Army would be voluntary by any able bodied citizen in the colonies. The Continental Army was expected to work in-conjunction with state-controlled militia units. The plan was for the state militia forces to be called out as needed in-order to supplement the Main Continental Army. Unfortunately, Washington found the process to be inefficient in strategic planning or for time sensitive engagements using ill prepared state militia.

The First Establishment of 1775:

In direct response to the Battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19th 1775, the Second Continental Congress resumed the responsibility for the volunteer troops raised in the colonies of Connecticut, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island. The force adopted on June 14th 1775, amounted to 39 regiments of infantry, 1 regiment of Artillery, and 1 separate company of Artillery. This would be the foundation to the birth of the Continental Army. Along with assuming the responsibility for these troops, Congress also voted to raise additional troops for the national defense. It called for ten companies of “expert riflemen” to be raised in the colonies of Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Virginia. This was a transitioning order that differed from the past when they merely adopted militia units already raised by the states.

Five days later on June 19th 1775, the Continental Congress would commission George Washington as Commander in Chief of the newly raised Continental Army. George Washington was chosen over other viable candidates such as John Hancock based on his previous military experience serving in the British Army. He was also seen as a prominent Virginia political statesman who the other colonies could easily unite under. After receiving his commission, he left for Massachusetts and assumed command of the Continental Army in Cambridge on July 3rd 1775.

A Second Force was also raised by the Continental Congress in July of 1775. This would be a smaller force specifically created to defend New York under Major General Phillip Schuyler. The mandate authorized by Congress allowed General Schuyler to launch preemptive attacks, which ultimately instigated the invasion of Canada on August 31st 1775. It wasn’t long before the Southern colonies like Virginia’s Lord Dunmore’s 2nd Virginia Volunteer Regt. saw active service as a supplemental force to the Continental Main Army.

The Second Establishment of 1776:

At the end of 1775, General Washington still had his forces at the Siege of Boston, and the attempt to capture Quebec City failed. To continue forward with the war the Continental Congress voted to re-raise the army at Boston and maintain Continental State Militia forces elsewhere. The Second Establishment would serve from January 1st to December 31st 1776, and be organized into 27 infantry regiments created from new units and reorganizing existing units. After January 17th 1776, the Army would be placed under specific theatre departments. The Canadian Department established January 17th 1776, the Middle Department February 27th 1776, the Southern Department established on february 27th 1776, the Northern Department April 14th 1776, Eastern Department established on April 14th 1776.

The Third Establishment 1777 to 1784:

*

Crown Insignia Buttons Make their Appearance Early on

************** Provincials & Loyalist Volunteers Join Ranks *************

************* 2 *************

Unknown British Service Button

Crown Surmounting initials FDM

Cast Pewter, Circa. early 1770’s

************* Unknown *************

With the RRN, RM,FDM, and CN buttons we might have a starting point into the American theatre by the British through Provincial service. As noted in a recent conversation with Don Troiani, these buttons do not have any records of the specific use for these buttons and we don’t know who wore them. So, any evidence I put forth is just speculation on my part about who could of worn these buttons. We know that Royal governors did raise Provincial and Volunteer forces to counter rebel activity and try to put a halt to the growing Revolutionary Movement. With the bulk of the British Army’s forces in the European theatre, the British regulars were short in numbers and only had a few strategic garrisons spread-out through New England and Canada.

Rhode Island Royal Navy

Rhode Island Royal Navy

************* Theory *************

*************

*

We know that Royal Provincials “RP” buttons by requisition records appear in 1780, but we don’t know for certain if they were used slightly before this time. The buttons below “could” have been a sort-of prototype for later “RP” buttons; Since, military style buttons outside of numbers were just making it’s entrance in England. They use an identical style design with a Georgian crown symbolizing service to the King, which is surmounting the particular designation of the buttons meaning use. Using this line of design correlation these groups of buttons would date to slightly before or after 1780. They were made specifically for a certain dynamic service to the Royal Governors of the New England colonies under the King’s authority.

If we date the button prior to just prior to the outbreak of the Revolution, we can theorize that there was some kind of preemptive military measure taken outside of the regular British Army in light of the Patriot movement. In this line of reasoning, King George III would have utilized the Royal Governor’s authority to organize either Provincial or Volunteer militia forces to assist General Gage’s garrisoned troops, as well as and the Royal Navy troops stationed in Rhode Island. The wearer of these buttons could have acted as a pseudo law enforcement under the Royal Governors authority to assist town officials who had to carry-out their duties under public resentment and hostility. The button’s crown acts as a reflection of service and legal authority under the King’s authority.

The Crown / RNN could mean RhodeIsland Royal Navy, Crown /RM could mean Royal Marines, as well as a province’s Royal Magistrate. There is no way to be certain without some kind of written record. The only one we know for certain is the Crown-CN buttons were ordered by the Colony of New York Committee of Safety, and the “CN” represents the Colony of New York. These buttons were thought to be given to early New York Regiments and have been found on sites prior to 1781.

Dale Hawley’s Research

************* Theory *************

Rhode Island Royal Navy: After doing an extensive search I found a Pawtucket Rangers out of Rhode Island = RIR for Rhode Island Rangers. This militia was formed in several towns, and just not Pawtucket. We also found that there was a 1st Rhode Island Regiment = RIR, which consisted of Negro’s and Native American Indians, but the waves under those initials indicate Navy or was a symbol for Rhode Island depicting three waves. The RNN I can’t make work with written records trying Rhode Island Newport Navy at the start of the Rev War 1774 to 1775.

I find it interesting the first Commander of the Continental Navy was out of Rhode Island Marines, again I thought 1775 to 1776 have to double check the dates. All of these buttons were made just prior to the start of the revolution. These would not have been regular British Army regimental issue, * but a precursor of sorts. (Probably, just months short of the introduction of the Crown over the “CN” Colony of New York buttons). I believe the mold was made around 1774 to 1775. Rhode Island started a Navy and the colonists for intensive purposes were still British subjects. It would only make sense that the design pattern and inscription would be RRN = RhodeIsland Royal Navy. Since, all of these patterns were found in New York and New Jersey areas along the Hudson River it would make sense for the outbreak in 1775 to 1776. The problem is seafairing men never wore pewter buttons and they always brass. Pewter is a soft metal and does not hold up to the rigors or hardship labor of a sailor’s life at sea. Although a lead mold made from a brass original would produce a replica of these first Royal “RhodeIsland Royal Navy” buttons while they are on land and that is exactly where 99% of all Americans fought the British. I’m not mis-spelling Rhode Island. You need to think outside the box for the buttons design pattern.

Rhode Island Royal Navy

Rhode Island Royal Navy

Continental Navy, Pewter Continental Navy, Y. M.

~ June 29th 1776 ~

John Lawrence ~ Pays Captain Jehiel Meigs £172,

to enlist a Company in Boston for Service in the Continental Army.

************* ************* ************** ************* *************

Shortly before the Declaration of Independence was signed, the Second Continental Congress was already moving ahead with their preparation for War. Congressional Department Committees were being formed, and money was being sought by Cause Benefactors. Money for enlistments, weapons, rations, and supplies, were needed for the new Continental Army.

Continental Army & Militia Infantry Weapons

************** Muskets, Long rifles, & Bayonets *************

************* 2 *************

The Brown Bess

The Brown Bess is a muzzleloading smoothbore musket. The musket would fire a single shot ball, or a cluster style shot that fired multiple projectiles giving the weapon the so called, “Shotgun” effect. There was two variations of the Brown Bess. The Long Land Pattern, and the Short Land Pattern. .75 caliber.

The Brown Bess is a muzzleloading smoothbore musket. The musket would fire a single shot ball, or a cluster style shot that fired multiple projectiles giving the weapon the so called, “Shotgun” effect. There was two variations of the Brown Bess. The Long Land Pattern, and the Short Land Pattern. .75 caliber.

The Charleville Musket

The Charleville Musket was a standard .69 caliber French Infantry Musket. There was a large number of Charleville Model 1763 and 1766 muskets imported into the United states from France because of Marquis de Lafayette’s influence.

The Charleville Musket was a standard .69 caliber French Infantry Musket. There was a large number of Charleville Model 1763 and 1766 muskets imported into the United states from France because of Marquis de Lafayette’s influence.

18th Century Brass Gang Bullet Mold for a 69 Caliber Shot.

18th Century Brass Gang Bullet Mold for a 69 Caliber Shot.

American Made Committee of Safety Muskets

After the war broke out a lot of muskets were produced by various gunsmiths in the colonies. Long Rifles such as, “The Pennsylvania Rifle or Kentucky Long Rifle”were used by snipers and light infantrymen. The long rifle was first introduced by German gunsmiths operating in Pennsylvania. They were able to modernize the existing musket by introducing a spiral groove on the inside of a rifle barrel. This modification increased the range and accuracy by of the rifle by spinning a snuggly fitted ball. A spinning ball was found to be more stable in its trajectory, and therefore more accurate than a projectile that does not spin. This was a big improvement over the traditional smoothbore barrels. The rifled barrel was also able to accurately increase its range up to 300 yards compared to 100 yards from a smoothbore musket. There was some drawbacks to the long rifle, they could not be fitted with a bayonet, and the complicated loading process took valuable reload time in firefights.

American & French Model Bayonets used by Continentals & Militia

The Continental Army and State Militia units were in most cases not equipped with a bayonet as part of their enlistment. British infantrymen were furnished with a bayonet as part of their standard gear, which in most cases was stored in their side pouch until instructed to place on their rifles. After engagements some American soldiers who used Brown Bess muskets were known to claim bayonets off of fallen British soldiers. The Bayonet was fixed on the end of the musket, and often acted as their primary weapon due to the long loading times, limited range, and poor accuracy. The bayonet became the soldiers front line of defense during hand to hand combat, or when one or both sides charged each other. The triangular shape of the bayonet was specifically designed to create a deep puncture wound that could become easily infected.

French Model 1766 Bayonet

This bayonet fit around the barrel of the gun, which allowed the soldier to fire while attached.

*

America’s Continental Army Begins to Muster Regiments

************** Continental Army Insignia Buttons First Appear *************

************* 3 *************

~ Victi Vincimus ~

A good general not only sees the way to victory, he also knows when victory is impossible. In war we must always leave room for strokes of fortune, and accidents that cannot be foreseen.

Intertwined Block Letter USA Button

W/ Raised Pie Crust Edge Border

Cuff Size 19.8mm Cast Mold Pewter, 1- Piece

*************

It is unclear when the first USA pattern buttons appeared, but we know Congress authorized the production of these buttons fairly early on and we’re in use by 1777. The intertwined USA button was designed specifically for Continental service, and they were issued to every branch and regiment either loose or sewn onto their uniforms. The intertwined USA button offered an inclusive style pattern, which provided a military service commonality, and allowed state soldiers to use them with their own specialized state buttons. A brass gang mold found at Independence Hall in Pennsylvania, shows us the molds were cut by professional artisan button makers, and then produced in large quantities in government contracted workshops. There are over 40 style USA button patterns, which can only be differentiated by size and shape of the letter cuts. This was probably due the new molds replacing worn out molds after large numbers were manufactured. We also know that other local artisans in upstate New York in the Fishkill barracks and in Connecticut Village supplied similar block style intertwined USA buttons. These also appear to be slight variations in letter style from the original gang mold found in Philadelphia. Some earlier USA patterns found in-use prior to 1780, appear to have more slender lettering. Thicker block style letters seem to appear from sites post – 1780.

One of only 2 known USA Button Molds known to exist. The Mold depicts an

One of only 2 known USA Button Molds known to exist. The Mold depicts an

intertwined USA Script Pattern, which is believed to be produced towards the

tail end of the Revolution circa. 1783-84. There has never has been any of these

Script style buttons found by archeologists on any campsites or battlefields.

************** ************* *************

The soldiers who enlisted in the Continental Army were colony Patriots who fought for the “Cause of Independence.” The standard enlistment period ranged from one to three years, and the men were paid, rationed, and supplied with uniforms that had intertwined USA pattern buttons. A private would make $6.23 per month and his pay would increase with promotion. Most men who served in the Continental Army were between the ages of 15 and 30 years old. Sometimes a promotion in rank brought an increase in a soldier’s food rations, and in some cases money was in lieu of their food rations. In the beginning of the war, enlistments were curtailed to a year’s duration, as the Continental Congress feared the possibility of the Army evolving into a costly permanent standing army. In 1778, congress changed the rules and men could either serve three years or the duration of the war.

The Intertwined USA Dated 1777 Button (Thicker Letters)

Continental Army Enlisted Man’s Pattern Found in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania.

This Pewter Cast Button is Coat Size 20mm. with a Loop Shank.

************* ************* *************

This intertwined dated 1777, USA button would have been worn by a Continental Army soldiers who took winter quarters at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. Valley Forge functioned as one of the eight military encampments used by the Continental Army’s main body. After the British captured Philadelphia on September 26th 1777, Washington was not able to recapture America’s new capitol city. Washington who was unfamiliar with the territory surrounding Philadelphia asked for his generals recommendation on where to winter quarter the Continental Army. In addition to their strategic recommendations, he also had to contend with input from politicians of the Continental Congress and Pennsylvania state legislators who expected the Army to select an encampment site, which could protect the countryside around Philadelphia. Considering all the political and strategic dynamics, Washington choose Valley Forge, which was approximately 18 miles northwest of Philadelphia. Valley Forge’s location allowed for quick troop deployment to protect the countryside, and its higher altitude flat ground meant that any offensive attack from the British would prove difficult. This would be the new home for 12,000 of George Washington’s Troops.

The Intertwined USA Dated 1777 Button (Thinner Letters)

Continental Army Enlisted Man’s Pattern, Slight Pattern Difference.

Excavated by BRAVO at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania.

This Pewter Cast Button is Coat Size 20mm. with a Loop Shank.

************* ************* *************

This intertwined dated 1777, USA button is one of two dated mold patterns found. This button would have been worn by a Continental Army soldier who took winter quarters at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. The six month encampment in Valley Forge, PA. was a major turning point in the American Revolution. George Washington arrived with 11,000 Continental regulars six days before Christmas in 1777. Provisions were short in supply, and cold weather conditions were extremely harsh for his improperly clothed soldiers. Washington’s troops constructed somewhere between 1,500 to 2,000 log huts that measured approximately 14 x 16 feet. This would allow the 400 women that accompanied the troops and soldier’s families who arrived to be with their spouses. In addition to the huts, his troops built miles of trenches, military roads, and paths. This ended-up being more than an encampment, it was a small city of constant activity. On the political side, certain members of Congress wanted to replace Washington for his strategic losses. Some previously politicians who originally backed him were now calling him incompetent. The one positive measure would be the transformational roots of the Continental Army into a properly disciplined and trained fighting force. General Washington would enlist the service of former Prussian military officer Friedrich Wilhelm Barron Von Steuben to properly instruct military drills to fellow officers who in-turn trained the bulk of Washington’s Army.

USA-Made Roman Font (Intertwined) USA Button

Continental Army Enlisted Man’s USA Pattern of 1780

Waist Coat Size 18-19mm. White Metal or Pewter, 1-Piece

************* ************* *************

This is the small size “borderless” intertwined USA pattern used by enlisted men. This button appears to have been made by local artisans familiar with button making. This borderless style button has been found in South Carolina and Fort Anne New York, and dates circa. 1780’s. Collectors should note the borderless style difference in the intertwined USA pattern of this button and the ones purchased from the French issued in 1782. The French borderless style only intertwines the US, and the A is left detached.

The Battle of Fort Anne was fought on July 8th 1777. Several days earlier General Burgoyne was surprised by the news that the American Army withdrew their forces from Fort Ticonderoga. He hurried as many of his troops forward in pursuit of the retreating Americans, and the remainder of his forces would drive forward toward Fort Edward. The British caught up to the retreating American Army and encamped about 3/4 of a mile north of Fort Ann. The Americans decided to surround and attack the British while they had the numerical advantage. The British were outnumbered, and sent for reinforcements. The Americans would have most probably captured the entire British forward force, but they fell back to Fort Anne because they fell for a rouse produced by British war whoops, which indicated reinforcements were close. As more of Burgoyne’s Army came down the road in support the Americans took the preemptive steps and retreated from fort Anne to Fort Edwards.

North Carolina Volunteers

Intertwined USA Regt. Button

Cuff Size 17mm. One-Piece Cast Pewter Mold

************* ************* *************

North Carolina Regiments fought in both the Northern and Southern theatre during the American Revolution. On March 7th 1777, three companies of NC Light Dragoons were placed on the Continental Line. Later, on July 10th 1777, two companies of NC Artillery were placed on the Continental Line. On March 7, 1777, the Continental Congress approved placing three companies of NC Light Dragoons onto the Continental Line, not to be assigned to any existing regiment. North Carolina Continentals performed well throughout Washington’s Northern campaign, afterwards they were dispatched to help General Benjamin Lincoln in South Carolina and Georgia. By June of 1779, the 2nd Company of NC Artillery was disbanded. On May 12th 1780, the British accepted the surrender of General Benjamin Lincoln at the siege of Charleston, South Carolina, which included almost all of North Carolina’s Continental Troops under his command. Sometime afterwards four regiments of NC soldiers reconstituted and continued on to support Major General Nathanael Greene in South Carolina until he furloughed them in the spring of 1783.

Intertwined Block Letter USA Button W/ Raised Pie Crust Edge Border

Continental Army Enlisted Man’s Pattern is Found on 1780-82 Sites

Cuff Size 17.8mm Cast Pewter, 1-Piece

************* ************* *************

General George Washington’s Continental Army consisted of several successive armies. By 1783, most of the Continental Army was disbanded in hopes for a Paris Peace Treaty. General Washington and his remaining Generals encamped the Continental Army’s last 7,200 troops at New Windsor’s Cantonment, West Point Area, as well as several mountain areas around the Hudson River. The 1st and 2nd Regiments went on to form the nucleus of Wayne’s Legion 8 years later in 1792 under General Anthony Wayne. This became the foundation of the United States Army in 1796. George Washington had to fight for this because he did not want our country to be at the mercy of hired European mercenaries. A little known fact is that the army never numbered more than 17,000 men. Turnover proved to be a constant problem for General George Washington, especially in the winter of 1776–77. This high attrition rate was the cause for the Second Continental Congressional Board of War to approve longer enlistments. The USA button was the most universally used button and found on Revolutionary War sites throughout the 13 states.

Officer’s Pattern Overlaid USA Pattern button

French Design Mirroring French-made Belt Plates & Infantry

Hangers brought by Lafayette for the men of his Light Division

Silvered Pewter Repousse 26.5mm Wood back, Cat Gut Cord

************* ************* *************

Major General Marie Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier de La Fayette was born into a privileged life in an expansive chateau in Chavaniac, France on September 6th 1757. To the public in the United States he was simply known as Lafayette. In 1772, King George III’s younger brother Prince William Henry The Duke of Gloucester revealed that he secretly married Maria, Countess Dowager of Waldegrave. King George III did not approve of the marriage and barred them from the Royal presence. Sometime afterward Prince William was a guest of honor at a dinner party in-which the young Lafayette was attending. William was still angry about his censure and began lashing-out about his brother’s political policies in the American colonies. In a vengeful arrogance against his brother the king he praised the colonists anti-British rebellion and gave his admiration for their fortitude and courage in the opening battles at Lexington and Concord. The young ambitious Lafayette whose father had died in the Seven Years War fighting the British received all the inspiration he needed to fight back against the British Empire.

French-Made Roman Font (Partially Intertwined) USA Button

Continental Army Enlisted Man’s USA Pattern of 1781/82

Coat Size 27mm. White Metal or Pewter, 1-Piece Button.

************* ************* *************

After the dinner party with King George III’s brother it was said that Lafayette couldn’t think about anything else except joining th American Cause against the British. He was a highly motivated individual who only sought to get to America no matter what the personal cost. Some say he saw glory in joining the American Cause because it enabled him to fight against his archenemy and get vengeance for his father’s death. As soon as he arrived in Paris immediately started to make inquiries and preparation to voyage across the Atlantic to America. In 1777, after the Paris Peace Treaty, King Louis XVI really did not want to provoke Great Britain at this point, nor did he want to involve himself in what he felt was an internal civil war and just a British political matter. At one point he even issued explicit orders reflecting his intentions to all french noblemen who were sympathetic to the American Cause. Being young and arrogant Lafayette just ignored the King’s orders and eluded authorities to cross the Atlantic so he could join-up with the American Revolutionaries. At the time, Lafayette was still a young teenager who spoke very little English, and lacked any formal military training, nevertheless had any battle experience.

George Washington and Lafayette at the Battle of Brandywine on September 11th 1777.

George Washington and Lafayette at the Battle of Brandywine on September 11th 1777.

Oil on canvas, by John Vanderlyn. Picture courtesy of the Gilcrease Museum, usa OK.

************** ************* *************

Lafayette quickly joined the ranks within Washington’s Army and was said to be eager to fight in battle. He would see his first action at the Battle of Brandywine near Philadelphia. Lafayette was shot in the leg, but he showed courage and was able to organize a successful retreat of his fellow soldiers. Following a two month recuperation, he was given command over his own division. Lafayette endeared himself to General Washington and would stay with him from the winter quarters of Valley Forge in 1777, all the way to the Siege of Yorktown in 1781. Washington definitely took to the young Lafayette as a son, and the Frenchman considered Washington as both a friend and a father figure. General Lafayette died in Paris on May 20th 1834, at 76 years old. He was known by the citizens of the world as the “Revolutionary Hero of Two Worlds.” In his will he requested that he be buried in both American and French soil. His son fulfilled his request and placed dirt on his coffin taken from Bunker Hill.

French-made USA Enlisted Man’s Pattern of 1781/82

Raised Letters S Overlaps U, A Separate on Plain field

1-Piece, 27mm. Coat Size. White Metal or Pewter.

************* ************* *************

In 1778, the first order for USA buttons was from a Congressional requisition in April of 1778, for 100,000 suits of clothes. The USA buttons were supposed to have roman intertwined letters and be made of Block Tin or Brass with a strong eye shank. White buttons would be made for wagoners and drivers. In 1779, the French gave a written estimate, which was a modified version of the original order stating that White buttons would be made in Pewter, or white metal, and yellow ones of brass. Ten thousand uniforms were made in 1779, stockpiled and then shipped aboard the Marquis de Lafayette. Unfortunately, the British captured the ship and the uniforms and buttons were sold as a prize in an auction in London. We don’t know if any brass buttons were made and shipped with this order. Another order arranged by Colonel John Laurens in France on April 26th 1781, included 300 gross of white metal buttons for coats, 25 gross of yellow buttons, and another 300 gross of white metal buttons for waistcoats and this order was filled and delivered. Later in August of 1781, the final shipment arrived in Boston which contained 1,200 dozen of the large USA buttons, and 1,200 dozen of the small white stamped metal buttons. This shipment would include the “Borderless Style USA Buttons,” which are found throughout the Hudson Highlands in NY. It is believed that this style button was not shipped out of military stores until sometime in 1782.

French-made Partially Intertwined USA Continental Service button

Continental Army Enlisted Man’s USA Pattern of 1781/82

Small Size 18mm. One-Piece, Dug in Virginia

************* ************* *************

Like radical university professors in 18th Century Scotland and the anti-British (Jacobite Sympathizers) underground movement in England, France was a seedbed of Enlightenment liberal ideologies. In the beginning of the American Revolution, non-official government French merchants would ship supplies to the Continental Army. Unfortunately, this was too limited in supply and Congress needed to have formal help from France’s government. Congress considered France’s official military supply chain vital for America’s Cause. Congress would immediately send envoys to France a few months after the war started in December of 1775, with Julien Bonvouloir and met with a Committee of Secret Correspondence. Unfortunately, nothing came out of it except an open communication window. In early 1776, Silas Deane was sent to France in hopes of seducing the French government to lead aid to the colonies. This gained some French sympathy and he was able to secure a shipment of arms and ammunition. He was also able to enlist a number of Continental soldiers of fortune, including Johann de Kalb, Thomas Conway, Casmir Pulaski, Baron von Steuben, and Lafayette! All notable figures who would make great contributions to the revolution and be of great assistance to George Washington. Benjamin Franklin would be dispatched to France in December of 1776, as Commissioner for the United States and would stay until 1785.

With Washington’s victory at the Battle of Saratoga hope was brought back to the Patriot movement and newly developed enthusiasm in France. This realization that Americans could be victorious spurred France to formally recognize the United States with the Treaty of Alliance in 1778. This would be a momentous shift in support from private French benefactors to the French government resources. The treaty allowed the country of France to provide formal funding and send supplies, equipment, and weapons in a military supply management system to the Continental Army. By war’s end France accumulated over 1 billion livres in debt, which partially caused her own revolution.

This NC USA was found along the banks of the town Creek in Brunswick County, N.C. March 2011.

Allen Gaskins said there was a skirmish there when Cornwall came up from S.C and took Wilmington, N.C.

************** ************* *************

There is no way to be certain how many gang molds were made with slight letter variations in the intertwined USA buttons. The importance was placed on national affiliation, as well as any kind of misappropriation of government stocks of clothing. Below is a handful of pattern designs found to be made throughout the war. I was personally able to account for 41 known American & French made intertwined USA buttons.

*

* *

* *

* *

* *

* *

*

The Continental Army Regiments of 1776

************** Continental Army Numbered Buttons First Appear *************

************* 3-A *************

*

General George Washington Commander in Chief of the Continental Army provides General Orders for Regiment uniforms and buttons on November 13th 1775.

*************

“The Colonels upon the new establishment to settle, as soon as possible, with the Quartermaster General, the uniform of their respective regiments, that the Buttons may be properly numbered, and the work finished without delay.”

************* ************* ************** ************* *************

The Main Army of 1776

At years end of 1775, General Washington had made little stride in the Siege of Boston, and his Army’s attempt to capture Quebec City in Canada failed. On December 30th, General Montgomery and Colonel Benedict Arnold who were two of Washington’s greatest assets made an un-calculated foolish attempt in the harsh weather conditions to capture Quebec city because their troops enlistments were coming to end-term in two days. General Montgomery’s plan was to scale the walls during the night in a snowstorm undetected. Unfortunately, Colonel Arnold was wounded, Daniel Morgan was taken prisoner, and General Montgomery was killed instantly at close range by a Grapeshot wound to the head.

General Washington desperately understood that he had to keep his Army of state volunteers intact if the Cause for American Independence was going to be successful. At the end of 1775, the reality of expiring troop enlistments was on the forefront of his mind. At the end of December he was able to successfully convince a good number of soldiers to overstay their enlistments. Washington understood that Congress willfully limiting enlistments for a year was going to hinder the success of his campaign’s Departments. General Washington corresponded with Congress suggesting that they would need to expand the one year limit duration for enlistment service.

The Second Establishment in January of 1776

In order to continue with the war effort the Continental Congress had to vote to re-raise the Army at boston and maintain Continental state militia volunteer units. By year’s end of 1775, the Continental Congress was supporting units from every state except for Maryland. Washington’s year-end request for an extension of enlistments went unchecked, by fearful Congressional leaders worried about the costs of supplying and maintaining a large Army. The new enlistments would once again only serve a one year term, which started from January 1st to December 31st 1776. To help address the lack of state cohesiveness within the Main Army, Washington issued a General Order on January 24th 1776. It stated that the State Units would be re-organized and redesigned into numbered Continental Regiments. The Main Army would now consist of 27 infantry regiments. (There would be no separate Artillery unit until Harrison’s 1st on November 26th 1776)-( There also would be no Dragoon’s unit until the 3rd establishment of 1777). They would be organized from the new enlistments in Boston and the existing state units whose volunteers were encouraged to continue on in supporting the Cause for Independence. Each of the Continental Regiments would be comprised of 8 companies with 728 men. Of these, 640 men of lower rank would provide the front line musket firepower and the rest were officers and their staff.

The 5th Continental Regiment was organized from the

1st New Hampshire Regt. on January 1st 1776. This 1-Piece, 17mm

Pewter Cuff Button Depicts a Large Arabic Style “5” in the Center

************** Red Wool for British Uniforms is Dyed Brown *************

The 1st New Hampshire Regiment was an early infantry unit formed under Commander John Stark on May 22nd 1775. The unit fought in the second military engagement of the Boston Campaign at Chelsea Creek on May 27th & 28th 1775. Afterward, they fought at the Battle of Bunker Hill in Charlestown Massachusetts on June 17th 1775. While actively taking part in the siege of Boston, the unit was renamed the 5th Continental Regiment. Later in the spring, the 5th regt. was sent to Canada where the New Hampshire soldiers fought on June 8th 1776, at Trois-Rivieres. Under Brigadier General William Thompson they attempted to stop the British advance up the Saint Lawrence River Valley by Quebec Militia forces under Guy Carlton. Afterward, they helped defend the area around Lake Champlain. Later in the year, the 5th Continental was transferred south to George Washington’s main army where it fought at the pivotal Battle of Trenton on the morning of December 26th 1776. On January 1st 1777, the unit was renamed the 1st New Hampshire. Shortly afterward on January 3rd 1777, the regiment had a small victory at Princeton and then sent back to the Northern Department.

The 8th Continental Regiment was organized from the

2nd New Hampshire Regiment under Colonel Enoch Poor

Pewter, 22mm. Coat Button, which depicts an Arabic “8” in the Center.

************** Blue Faced Scarlet & Scarlet and White *************

Shortly after the Battle of Lexington & Concord the Massachusetts Provincial Congress called upon other New England Colonies for their assistance in raising an army of 30,000 men. On May 22nd 1775, the New Hampshire Provincial Congress answered their call and voted to raise a volunteer force of 2,000 men. Volunteers from southeastern New Hampshire and western Maine answered the call to arms in order to join the Patriot army in the siege of Boston. The New Hampshire Provincial volunteers were organized into three regiments and each made-up of ten companies. This 2nd New Hampshire Infantry Regiment was commanded by Colonel Enoch Poor from Exeter, New Hampshire. Colonel Poor was sympathetic to the separatist movement ever since the introduction of the Stamp Act of 1765. He was also an elected official of New Hampshire’s Provincial Assembly. His regiment immediately departed for Boston and arrived on June 25th 1775, which was shortly after the Battle of Bunker Hill. By the summer time Poor’s Regiment was absorbed into the Continental Army, and placed under the Northern Department. Poor’s regiment was assigned under Richard Montgomery’s and set out on his Canadian expedition.

The Green Mountain Boys was a Militia Unit made up of Vermont Settlers. The rebel group was formed prior to the

Rev. War in the 1760’s. The membership mostly consisted of relatives of Ethan Allen, who was their original leader.

On the onset of the war, The Green Mountain Boys under Allen marched north and captured Fort Ticonderoga from a

small garrison of British soldiers on May 10th 1775. Afterward, they dragged its artillery down to Boston for the Siege.

************** ************* *************

General Montgomery’s expedition would be composed of regiments from Connecticut, New York, and New Hampshire, as well as the Green Mountain Boys under the command of Ethan Allen’s cousin Seth Warner. The invasion force was led by General Schuyler whose strategy was to go up through Lake Champlain in order to begin the campaign with the attack on Montreal. Afterward, they would go on to Quebec. The troops of the 2nd New Hampshire played a key role in the Battle of Lounge Pointe and the Siege of Fort Saint Jean in September of 1775.

This was the Flag (colors) of the 2nd New Hampshire, which was captured at Fort Anne on

July 8th 1777, by an advance of General Burgoyne main army. Remarkably, the 2nd’s

Flag was kept as a war trophy instead of being burned or cut into strips for bandages.

************** ************* *************

On January 1st 1776, the 2nd New Hampshire became the 8th Continental Regiment. In May of 1776, the 8th Continental would see action in Carleton’s Counter offensive at the Battle of Trois-Rivieres. In July, they retreated south to Fort Ticonderoga and helped construct a new fort across Lake Champlain on Rattlesnake Hill. In November the New Hampshire units marched south and rejoined the rest of the Continental Army for the Battle of Trenton at the end of December. On January 1st 1777, the 8th Continental regiment was reorganized and resumed as the 2nd New Hampshire Regiment and went oh ahead to the Battle of Princeton on January 3rd. A little more than a month later on February 21st 1777, Colonel Poor was made a Continental Brigadier General, and Lieutenant Nathan Hale was commissioned as a Colonel and given the command of the 2nd New Hampshire in April. Three months later at Hubbardton Vermont, Colonel Hale and part of the 2nd regt. was captured by the British in a surprise attack while having breakfast. After Colonel Hale’s capture, George Reid assumed command of the remainder of the regiment who proceeded back north to Fort Ticonderoga. After the ordered withdraw of Fort Ticonderoga on July 5th, Reid’s 2nd went to Fort Anne in-which it lost its Flag (Colors) during the battle.

The 11th Continental Regiment was Reorganized from Colonel Hitchcock’s

2nd Rhode Island Regiment on January 1st 1777. This a 1-Piece, 22mm.

Pewter Coat Button, which depicts a Crude Style Arabic “11” in the Center.

************** Possibly Brown W/ White Facings *************

On May 6th 1775, shortly after the Battles of Lexington and Concord, the General Assembly decided to raise a brigade of three regiments. Colonel Daniel Hitchcock in the Rhode Island Army of Observation was authorized to raise a brigade of volunteers from County of Providence for service during the siege of Boston. Initially, the observation unit’s mission statement was to monitor the British Army’s strategic preparation for future hostile activities. Two days later on May 8th 1775, Colonel Hitchcock was able to raise eight companies of willful volunteers, which would end-up umbrellaed as one of the brigades under General Nathanael Greene; but still under the command of Colonel Hitchcock. In this early period the Continental Army did not have unit number designations, and was often called after the commanding officer. For the most part, Hitchcock’s Brigade ended-up expanding their duties and participated in the siege of Boston for the remainder of 1775. On June 17th the regiment would see action at Roxbury, Massachusetts during the Battle of Bunker Hill. On the 28th, the regiment was expanded to ten companies, and was adopted into the Continental Army when George Washington arrived in Cambridge to take command on July 3rd. On July 22nd the regiment was assigned back to General Greene’s Brigade. Later in the year, some elements of his regiment accompanied Benedict Arnold on his expedition to Quebec.

********** Charles M. Lefferts **********

On January 1st 1776, Hitchcock’s Brigade was renamed the 11th Continental Infantry. After the British evacuation of Boston in March the regiment was redeployed with the bulk of the Continental Army to defend New York City. Starting in August of 1776, the 11th Continental Regiment fought in the New York and New Jersey Campaign for the control of the Port of New York, and the state of New Jersey. The British forces under General Sir William Howe landed his force in Long Island and quickly defeated George Washington’s Continentals. General Howe was successful in driving Washington out of New York, but overextended his reach into New Jersey, and ended his active campaign in January of 1777. The last battles of the 11th Continental Infantry Regiment was on december 26th at the Battle of Trenton, and on January 3rd 1777, with the Battles Princeton. Afterward, the 2nd Rhode Island Regiment was ordered away to defend the Hudson River Valley where Colonel Hitchcock met his demise on January 13th 1777. Colonel Israel Angell was placed in command and went on to fight at the Battle of Red Bank, and the siege at Fort Mifflin. In 1778, the 2nd Rhode Island distinguished itself in the Battles of Monmouth, and in august traveled up to Newport Rhode Island for the siege on Aquidneck Island. From June of 1778 to December of 1780, the regiment was assigned to Stark’s Brigade in the Main Army, which was based in Morristown, New Jersey. Their last major engagement was the Battle of Springfield in 1780. Out of a strength of 160 men 6 were killed, 31 wounded, and 3 were reported missing. Afterward, there were several minor skirmishes before they consolidated into the 1st Rhode Island Regiment in 1781.

The 12th Continental Regiment was formed from

Colonel Moses Little’s Regiment of Massachusetts State Troops

Pewter, 22mm. Coat Button, which depicts a crude Style Arabic “12” in the Center.

************** ************* *************

Moses Little served in the Massachusetts Militia, and fought with his company at the Battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19th, 1775. Immediately afterward on April 23rd 1775, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress (Assembly) needed to answer the call of the Second Continental Congress and help supply and arm the Continental Army besieged in Boston. In the call to arms, the Massachusetts Assembly made Moses Little Colonel, and gave him the authority to raise a regiment in Cambridge for the newly forming Massachusetts State Troops. His Regiment would consist of 10 companies, and quickly become known as, “Little’s Regiment.” By June of 1775, the Continental Congress needed the newly raised states militia forces from New Jersey, New York, Maryland, and Massachusetts to help with the Siege in Boston. Colonel Moses Little Regt. would answer to their call on June 14th, and join the newly forming Continental Army. In July Little’s Regiment was assigned to Greene’s Brigade, which was an element of Washington’s Main Army.